Rape Culture, Then And Now: What Have We Learned?

Although there are a wide range of social issues that individuals are attentive to as the 21st century continues to unfold, rape remains the most important one to address and work towards resolving for millions of people around the world. Additionally, many individuals who do not view rape as the most significant social problem of our era still identify it as a deeply harmful reality which negatively impacts both the victim and the perpetrator. With these realities in mind, it is important to remain deeply engaged in the review of information which can provide us with detailed, accurate understandings of the issues that surface in context of sexual assaults as well as those which gain primacy after they have happened. In recognizing these realities and in attempting to develop solutions which lead to rape prevention and effective strategies which prevent revictimization and the normalization of sexual assault, we should consider the role that rape culture has played in impacting the way we think about this issue.

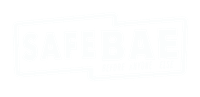

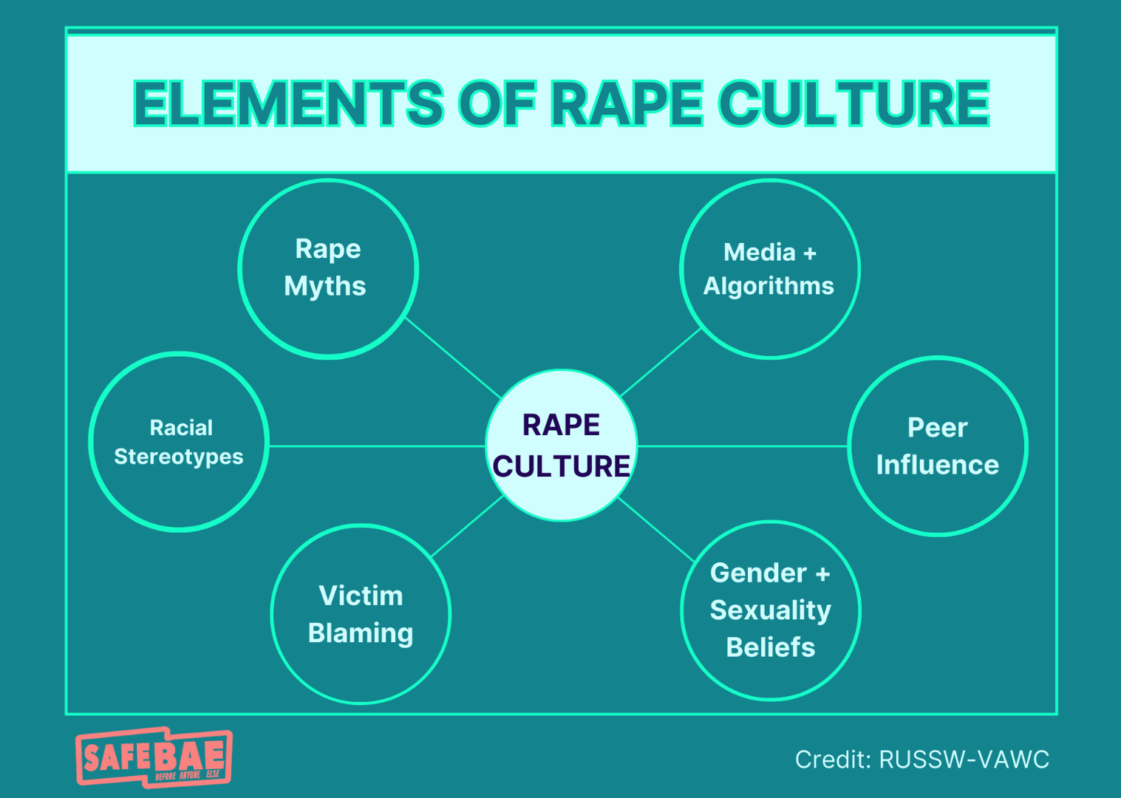

The term “rape culture” was coined during the 1970s but is not attributed to a specific person. Rather, it is associated with various activist communities, including radical feminists. (Radical feminism is an ideology which holds that patriarchy–defined as the domination of women by men–is the root factor leading to women’s oppression. In recognizing this principle, radical feminism maintains that society must be restructured at its core to end male supremacy. The process/praxis of the radical feminist ideology includes critiquing normative social institutions and practices, including sexuality, traditional family structures, and marriage given the role they play in operating as tools that sustain patriarchal power.) Although defined diversely, rape culture can be understood as a sociocultural environment where sexual assault is excused and normalized through the development and maintenance of specific practices, beliefs, and attitudes. When an individual or group is said to be a part of a rape culture, the statement indicates that their actions, attitudes, and/or behaviors contribute to the creation or sustaining of a world that legitimates rape as an appropriate or inevitable aspect of life. The presence and perpetuation of rape cultures is problematic for many reasons, one of which is that they contribute to the development of hostile environments for sexual assault survivors. Additionally, rape cultures reduce assent to the notion that when an individual rapes another person, the perpetrator–not the victim–should be held accountable for the violation.

Numerous texts surfaced during the 1970s which gave rise to consciousness regarding rape cultures. Thus while rape cultures have existed for centuries, specific phrases which encapsulated what they involved and entailed apparently did not. In their 1974 book Rape: The First Sourcebook for Women, Noreen Connell and Cassandra Wilson discussed the elimination of rape as a goal which would not crystallize without a radical transformation of society. This assessment pointed towards the role that communal values play in shaping the way people think about sexual assault and its cultural acceptability. For example, the authors note that sexual assault became a problem when women began to discuss their experiences with rape as children, adolescents, students, spouses, etc. In engaging in these discussions, women realized that sexual assault was not a rare event but rather a common, pervasive issue. Here, readers can locate the surfacing of public thought regarding the role that common experiences, shaped by culture, played in contributing to the normalization of rape. In addition to being connected to the concepts and arguments found in Rape: The First Sourcebook for Women, the term “rape culture” is associated with the documentary film Rape Culture. The film, produced by Margaret Lazarus and Renner Wunderlich, discusses key issues pertaining to sexual assault, including but not limited to patriarchal sexual fantasies and specific terms that have been utilized to understand the normalization of rape, such as rapism. Although defined diversely, rapism is generally thought of as a set of cultural and societal values which make sexually assault a morally acceptable act.

The historical period during which the term “rape culture” gained traction is referred to as the Second Wave of the Women’s Rights Movement. This era is historically significant for many reasons, including the fact that it unfolded during the same era as the Civil Rights Movement, a period marked by radical revisions of culturally entrenched ideas which worked to rationalize and sustain racism. The challenging of racism coexisted with the insistence that sexist ideas be acknowledged and condemned, and the Women’s Rights Movement played an integral role in doing so by advocating for the ERA, defending abortion rights, and more. The Second Wave was also marked by the onset of ongoing dialogue regarding sexual assault. During the 70s and 80s, conversations and public discourse regarding sexual assault placed primacy on challenging the notion that rape was a rare occurrence committed by perverts. Additionally, discourse regarding sexual assault sought to identify rape as an act rooted in the intent to be violent and claim power, with this concept challenging the notion that rape was a crime of sex or lust. The surfacing and circulation of the term “rape culture” also materialized in context of the need to establish and legitimate the presence of rape crisis centers designed to address and resolve the issues which gave rise to and normalized sexual assault. Even as women-led organizations and individual female people established these centers, many people began to realize that women were not and should not be held responsible for challenging rape. Rather, perpetrators should play an integral role in recognizing the harmfulness of their actions and designing solutions to address and resolve the psychological and physical suffering caused by their violent, violative behaviors.

While the term “rape culture” gained traction during the Second Wave of the Women’s Rights Movement, thereby bringing more attention to how sexual assault became a normative and acceptable reality in the minds of many people, our understanding of rape culture has evolved and become more nuanced over time. From the 1980s through the 2000s, emphasis has been placed on acknowledging:

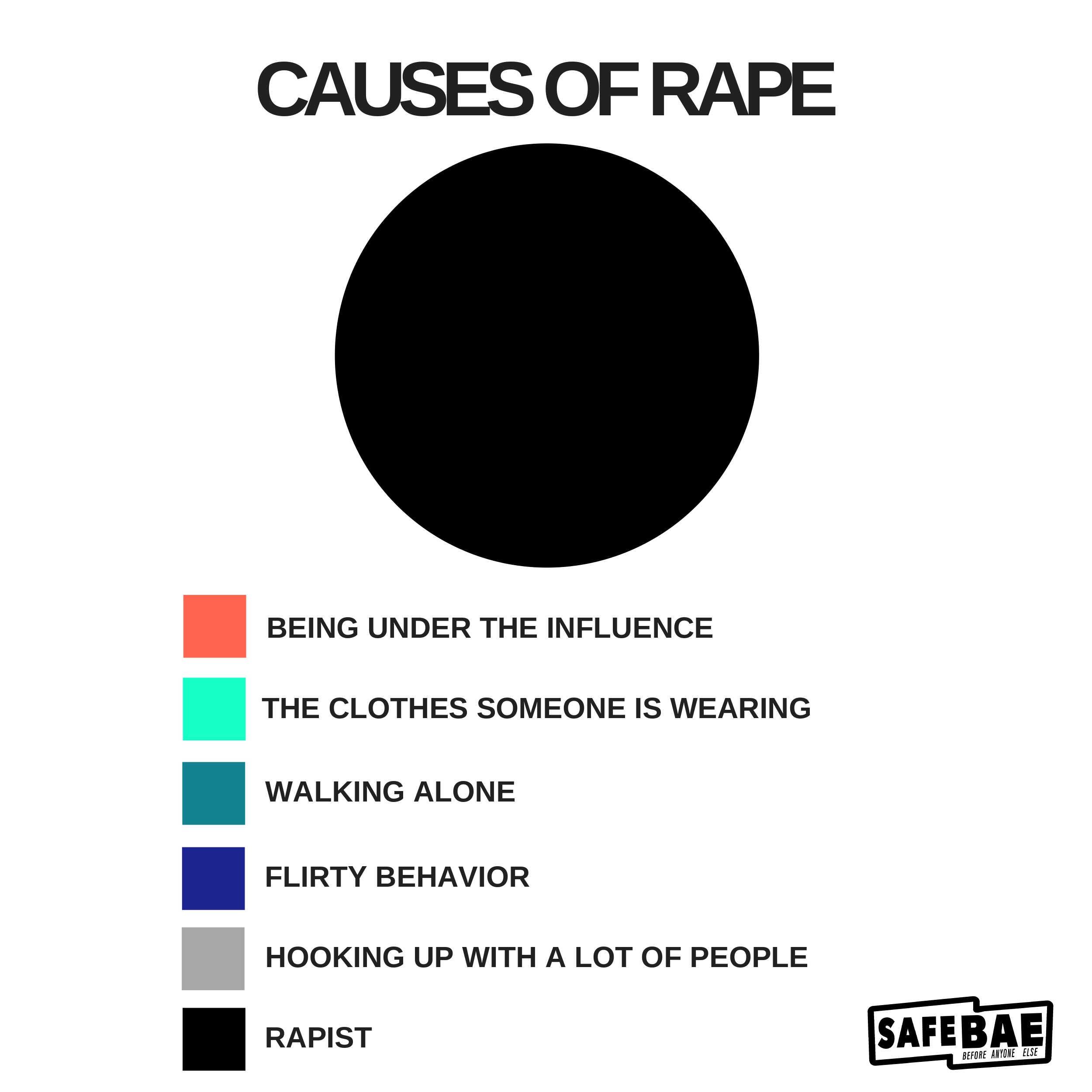

- Acquaintance Rape. Feminists, scholars, and activists worked to shift understanding of sexual assault away from the idea that these violent acts are primarily committed by strangers. In so doing, thinkers and activists worked to generate awareness that most sexual assaults are committed by an individual that the victim knows.

- Institutional Accountability. Activists worked to ensure that sexual assault was viewed as a personal and political issue, meaning that it must be addressed through public domains such as the legal sector. With this reality in mind, activists pushed for legislation such as the Clery Act. This legislation works to ensure crime reporting, the collection and reporting of crime statistics, and more.

- Violent Continuum. Understanding of rape expands and evolves to grasp sexual violence as an act which exists within a broader framework of problematic acts, including derogatory, sexist language, sexual harassment, and rape itself.

The progress made from the 1980s until the arrival of the 21st century–with progress being defined in terms of expanding and increasingly thoughtful discourse regarding the significance of rape–has continued. From 2010 until now, we have seen the following concepts and concerns emerge:

- Intersectionality. Contemporary understandings of sexual assault now engage an intersectional analysis which involves understanding how rape culture impacts individuals differently in light of key factors such as sexual orientation, gender identity, class, and race. The rise of the intersectional lens works to address the lack of attention that has been given to how multiple modes of oppression (such as sexism and racism) intersect in ways that increase the experience of harm in cases of sexual violence.

- Digital Activism. The 21st century has given rise to the presence of online movements such as #MeToo. Created by Tarana Burke in 2006, the movement went viral in 2017, the reality of which made rape culture a mainstream conversation. Other forms of digital activism include the presence of all types of feminist blogs and media platforms which centralize rape as a patriarchal act which must be challenged.

- Emphasis on Consent. Focus is now placed on understanding consent, with conversations including references to the distinction between nonverbal and verbal consent and the establishment of healthy boundaries in romantic and sexual relationships.

- Bystander Intervention. Emphasis is now placed on the role that bystanders can play in actively stopping rape before it unfolds and providing the victim with multiple forms of support and encouragement.

As time moves forward, it is the hope of anti-rape activists, legal advocates, and scholars that more and more primacy will be placed on acknowledging the reality of sexual assault. Additionally, we want to challenge sexist myths which prevent individuals from understanding how rape harms victims and masks the role that perpetrators play in causing harm. By working together and emphasizing nonviolent communication and challenging discourse as key to transformation, we can change society such that it becomes a safer and increasingly rape-free space.

Bio: Jocelyn Crawley is a radical feminist who resides in Atlanta, Georgia. She places primacy on analyzing and understanding sexual assault as an egregious harm. When she is not writing about these issues, Jocelyn enjoys reading, working out, and being with her church family.

Take Action

You can join the movement today:

Start a SafeBAE Chapter at Your School. We provide exactly what you need—step-by-step guides, training materials, and ongoing mentorship—so you can launch peer-led consent workshops, bystander intervention trainings, and survivor support groups on campus.

Access Our Survivor-Centered Resources. From lesson plans on healthy relationships to protocols for trauma-informed reporting, our free digital resources equip educators, parents, and students with the tools to believe survivors first and act safely.

Request a Program. Bring a SafeBAE expert into your classroom, community meeting, or parent night to share research-backed strategies and spark the conversations that protect young people.

Donate to Sustain Youth-Led Prevention. Your support ensures that SafeBAE’s free programming and education continues — so no survivor ever faces abuse alone, and every student has the chance to learn what consent really means.

SafeBAE is a 501c3 Not-for-Profit Organization